10. The times were a’changin for a controversial president

Date: 20 June 2016 Viewed: 24415

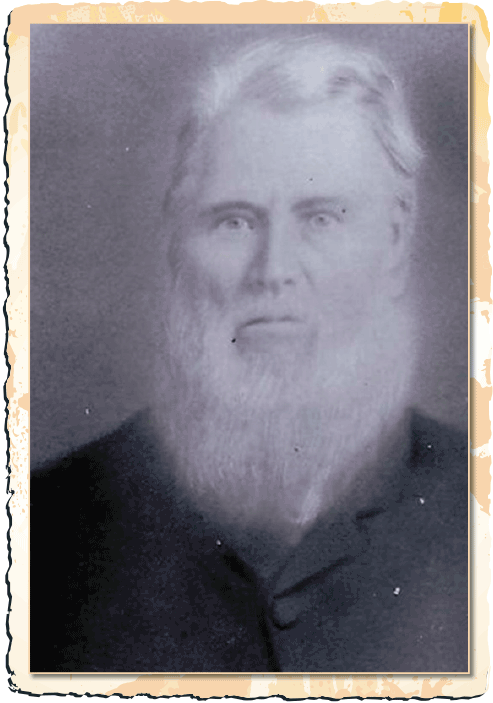

MW Pretorius was the son of the famous Voortrekker leader, Andries Pretorius. He was born on 17 September 1819 in Graaff-Reinett in the Cape Colony. At the age of 19 he joined his parents when the families embarked on the Great Trek to the north. In 1838, his father headed the expedition to punish the Zulu leader, Dingane, for the murders of the Piet Retief group. MW Pretorius joined him and formed part of the Boer forces at the battle of Blood River.

In 1839, MW Pretorius married Aletta Magdalena Smit and the couple had one daughter. They initially resided in the Pietermaritzburg area, but later moved to Potchefstroom where, after the death of his father, he became the new commandant-general of the district.

In 1852, the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republic (ZAR) came into existence when the United Kingdom signed the Sand River Convention and thereby recognised the independence of the people living north of the Vaal River. In 1857, MW Pretorius was elected the first president of this republic. One of his first tasks was to try and unite the various factions in the republic. To try and settle the differences about where a capital should be situated, he bought two farms on the banks of the Apies River. This new town would later become Pretoria, named after his father, Andries Pretorius.

Pretorius’s first encounter with the people of the Zoutpansberg may have been in 1864. The record states that he was present when the first minister of the Reformed church (Hervormde Kerk), Rev NJ van Warmelo, was welcomed on 30 July 1864. At that stage, President Pretorius probably did not receive a very warm welcome. A lot of the local residents supported Stephanus Schoeman in the battle for the presidency of the ZAR and a few years earlier, in 1857, even refused to accept the new flag, the Vierkleur.

Schoemansdal, the little town at the foot of the mountains, was an important part of the ZAR. Apart from its being the administrative hub of the republic, it also produced a significant amount of revenue through the trade in, among others, ivory. Joao Albasini, who had several teams of elephant hunters, estimated that between 70 and 80 tons of ivory were annually exported to Natal and the Cape Colony with a value of about £200 000. This excluded the ivory that made its way to what is now known as Mozambique.

More and more white people settled in the Zoutpansberg and in 1861 the town of Schoemansdal boasted 70 houses. When the town was at its busiest, some 100 families stayed there.

Along with the influx of people, the incidents of conflict escalated. The ZAR insisted that the various Venda chiefs pay “opgaaf” (tax) to the government. In 1855, a committee under leadership of Stephanus Schoeman decided that the chiefs should each pay, among others, five cattle and five elephant tusks per year. A number of government representatives, among them Joao Albasini, Michael de Buys and even a French citizen, JMA Logegary, were appointed to collect these taxes.

The conflict between the various Venda clans and the settlers grew in intensity and reached a boiling point when the Venda king, Ramabulana, died in 1864. His death caused a succession battle, with the main contenders being his sons Davhana and Makhado. Davhana immediately claimed the title and was also recognised by Albasini, the Native Commissioner at the time.

Makhado, with the assistance of the chiefs Madzhie and Nyakhuhu, attacked Davhana’s head-quarters and the latter had to flee. A lot of discontent existed among the Zoutpansberg people, with Albasini blaming people such as Magistrate Vercuiel for assisting Makhado. Albasini later offered protection to Davhana, much to the frustration of the new Venda king.

The ZAR’s executive committee, under leadership of Pretorius, must have had their hands full listening to reports and reading through correspondence explaining why the conflict continued. Makhado and Madzhie responded by launching attacks on the Schoemansdallers, while Albasini’s Tsonga warriors engaged in a war against Madzivhandila, another Venda chief.

The executive council of the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek. The photo was taken in 1857. In the front on the right sits Stephanus Schoeman and next to him is MW Pretorius. (Photo courtesy: Erfenis Potchefstroom)

In July 1865, Pretorius sent a delegation, comprising MJ Schoeman, CN Smit and GJ Verdoorn, to investigate and possibly put an end to the violence. Prior to their visit, a group of Zoutpansbergers, under leadership of Commandant SM Venter, reached a provisional peace agreement with Makhado and his “general”, Funyufunyu.

The ZAR delegation was later criticized for trying to meddle in affairs of which they clearly had little understanding. The Venda groups did not know or trust the delegation and a series of misunderstandings led to more attacks. When two of Makhado and Madzhie’s representatives, Fleur and Makoebie, appeared before the commission, they questioned the commission’s authority (because Pretorius and Kruger were not present). Both were arrested after appearing and placed in Albasini’s custody, which clearly did not promote an atmosphere wherein a peaceful settlement could be reached.

When the Schoeman commission left the Zoutpansberg at the end of July 1865, they seemed to have reached the conclusion that the conflict could only be ended by sending in a commando to subjugate the rebellious Venda chiefs. The manner in which the spoils of the war would be divided (which included the women and children captured) was also discussed. The commission did blame some white settlers for causing the conflict but, as far as could be established, did not propose any action against them.

The reality was, however, that the able men in the rest of the ZAR were not so keen on assisting their kinsmen in the Zoutpansberg to make war. The commando in Rustenburg, among others, did not have a lot of sympathy with the Schoemansdallers and reckoned they had caused their own problems by allowing their weapons to end up in the hands of the Venda tribes. They were also ordered by Pretorius to assist the burgers in Utrecht and Wakkerstroom with the wars that had broken out there.

President MW Pretorius had quite a busy period trying to extinguish fires throughout the ZAR. In August 1865, he convinced the executive committee to assist the Free State and declared war on Moshweshwe. Schoeman, who had to lead the commando to the north, was thus left without men and also without sufficient ammunition. Even the Waterberg “krygers” turned around when their commandant opted to rather go to Pretoria.

The next two years were marked by some vicious battles in the Zoutpansberg between the white residents, supported by among others the Tsonga warriors under leadership of Njakanjaka, and the VhaVenda. Chiefs such as Neluvhola and Magoro were attacked to weaken Makhado and Madzhie’s power. These attacks often met with fierce criticism from within the ZAR, because of the manner in which they were perpetrated. The battle against Magoro was one example of the extent of the brutalities.

A combined force of about 1 000 Tsonga warriors, accompanied by Albasini, joined the fight against Chief Magoro. The Zoutpansbergers were led by either Asst Cmdt Genl Geyser or Cmdt SM Venter. After some fierce fighting, the battle ended on 13 August 1865. More than 300 of Magoro’s men were killed, while 50 Tsonga warriors were wounded and two killed. After the battle, the Venda women were distributed among the Tsonga warriors, while the Boer fighters each received two children to be “booked in”. Only two members of the ZAR force, Alexander Struben and NT Oelofse, refused to take the children. More about these child slaves later.

The attacks by the Venda were on occasion brutal and merciless. A certain Hans Fourie was captured en route to Chief Lwamondo’s headquarters. His head was cut off and placed on a pole next to the road. It was later reported to the missionary, Stefanus Hofmeyr, that Chief Lwamondo used his skin as a “karos” (blanket).

Seeing that this story concerns MW Pretorius, we need to return to his role as president of the ZAR.

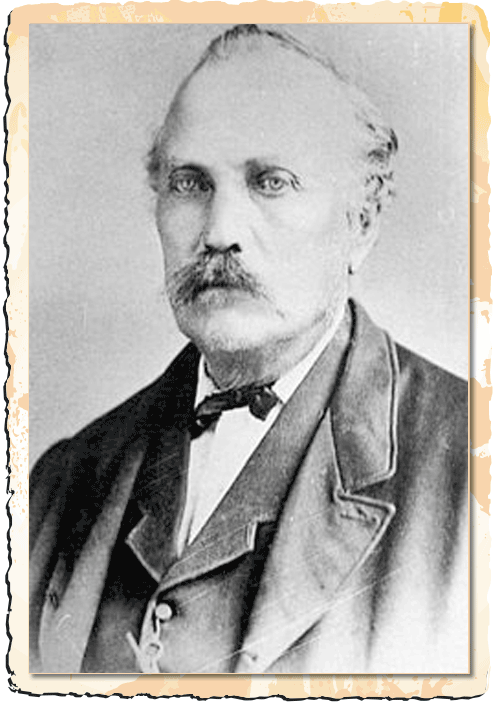

President M.W. Pretorius.

On 23 November 1865, the ZAR’s executive committee met and Pretorius and Kruger decided to “vrywillig de taak op zicht te nemen naar Z.P. Berg te gaan, ten einde al dat gene te doen, dat strekken kan zyn tot welzyn van dat District en te onderzoeken of een oorlog al dan niet onvermydelik is” (to go to the Zoutpansberg to establish whether a war was unavoidable).

The commission's executive council started with a series of hearings in Schoemansdal that lasted from 16 December 1865 to 3 January 1866. In one of the first decisions made, the captive Fleur (and probably Makoebie as well) was released. This opened the door for peace negotiations with the Venda leaders.

Pretorius and Kruger listened to a number of complaints against ZAR citizens and also considered previous reports about alleged abuses and transgressions of the hunting laws. On 29 December 1865, Chief Madzhie sent a message to the commission, indicating that he was in favour of a peace settlement. This gesture changed the sentiments and may have prompted the decision of Pretorius and Kruger to re-appoint people such as magistrate Vercuiel and Duvenage, who were known to be on friendly terms with Makhado.

The ZAR commission, unfortunately, never crossed all the t’s and dotted the i’s. They never met with Makhado or Madzhie and did not investigate the grievances against people in local leadership roles. Davhana was still under the “protection” of Albasini and, partly because of this, most Venda leaders refused to hand back any weapons to the ZAR.

Following a short period of relative peace, the conflict flared up again and the process repeated itself. The ZAR tried to get a commando together to fight against the rebellious Venda chiefs, but others in the rest of the republic were once again not so keen to help the Zoutpansbergers. Life in the Zoutpansberg became increasingly unbearable for all of its residents. President Pretorius played a final card to restore peace by sending Stephanus Schoeman, his son Hendrik, and SJ Meintjes to visit Schoemansdal and see what they could do. This mission also proved to be unsuccessful and it was clear that war was inevitable.

In May 1867, Commandant-general Paul Kruger started making his way with some 400 men to the Zoutpansberg. The battles that followed are, however, stories for another day. (Perhaps when we discuss Kruger Street). The end result was that the town of Schoemansdal was evacuated on 15 July 1867. Most of the residents, and even Kruger, left the town with tears in their eyes. Barely hours after their leaving the town, it was burnt to the ground.

MW Pretorius resigned as president in 1871 and was succeeded by the Dutch Reformed church minister, TF Burgers. For the next couple of years he moved out of the public domain and it was only in 1877, when the British annexed the ZAR, that he stepped to the fore again. Along with Piet Joubert and Paul Kruger, he formed part of the triumvirate that ruled from 1880 to 1883.

When Paul Kruger became president of the ZAR in 1884, Pretorius left politics. He moved back to Potchefstroom where he lived until his death on 18 May 1901.

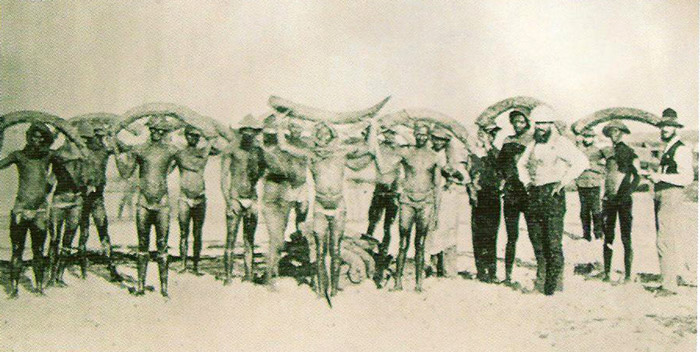

A scene very typical of the early Zoutpansberg: White ivory being carried by “black ivory”.

The story of MW Pretorius has another angle, which paints a much darker picture of his influence on the lives of the people in the Zoutpansberg. MW Pretorius, along with numerous other prominent people, also took part in the controversial “inboekeling” system, condemned in some circles as an excuse for child slavery.

To understand where it all came from, one has to go back all the way to the start of the 19th century, back to an era where the trading in slaves was an everyday occurrence. At the closest harbour to the Zoutpansberg, Inhambane, some 1 000 slaves were annually sold in the 1830s. The buyers came mostly from France, but some slaves were even shipped to countries such as Brazil.

Evidence of the extent of this form of trade is not difficult to find. When Louis Trichardt arrived in Delagoa Bay (Maputo) on 30 April 1838, he mentions in his diary that he had traded a horse for two child slaves. When commandant-general Andries Pretorius was victorious in the battle against Dingane in February 1840, he and his 335 men collected some 40 000 cattle as well as 1 000 children. These children were later “booked in” in Pietermaritzburg.

The trade in young slaves was also not a strange occurrence among many of the Black tribes. Women and children caught during wars were either subjugated or traded. Captured slaves, often referred to as “black ivory”, were sold to traders who took them to the various ports to be shipped away on dangerous journeys to other continents.

It was the system of catering for “foster children” that seems to have created the loophole for citizens of the ZAR to deal in child slaves. On 9 May 1851 a law was passed by the Volksraad, regulating the control of “apprentices”. The Apprenticeship Act mentions orphan children as well as gifts of children. The trading of children outside the border of the Transvaal was strictly forbidden. The Act made it possible to legally transfer children from one owner to another owner.

The children had to be registered with the Landdrost within eight days. A penalty of five rijksdaalers was payable for failing to do so. A fine of 50 to 500 rijksdaalers was payable for obtaining children illegally.

Initially the price for an “inboeksel” certificate was one rijksdaaler, the price of one-third of a sheep. The price was later increased to 35 rijksdaalers, the price of an ox. The certificate was sold together with the child slave. This made the trading in child slaves within the Transvaal border quite legal. The trading price to outsiders beyond the border was between 130 and 200 rijksdaalers (six oxen).

A person who has done a lot of research in the past few decades on the subject of child slaves is Dr JC van der Walt. He is the author of several history books, such as Child Slavery in South Africa 1837 – 1877. He writes:

"The documents that survived in the archives record the kidnapping of thousands of children in the district of Zoutpansberg during several wars and raids against the VhaVenda and the amaNdebele as well as the BaKwena people in the distant Bechuanaland.

Some of the kidnapped children were as young as four months old. The Boers targeted very young children because the babies would soon adapt to their new environment, forget their parents and would not abscond. Tribal chiefs also donated children.

The apprenticed children were valuable and the Boers treated them well. The older children that learned to speak Dutch or Afrikaans were affectionately called ‘Oorlams.’ However, thousands of children were ‘exported’, sometimes in an inhumane manner.

The Boers hired black hunters on foot to hunt elephants for them in the malaria and tsetse fly areas. The hunters returned with ivory as well as with ‘zwart ivoor’ or ‘black ivory’ - the euphemism for kidnapped children."

The trading in slaves was officially abolished by the British Government in 1834 and the slaves were “emancipated”. When the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republic became independent in 1852, the anti-slavery clause formed part of the Sand River Convention. This historic convention was signed on 17 January 1852 by MW Pretorius’s father, Commandant-General Andries Pretorius and others, on behalf of the new country.

Old habits, however, die hard and especially in the Zoutpansberg the demand for slaves created a profitable market and the practice continued. In terms of article four of the Sand River Convention, slavery in the ZAR was a very serious offence. However, the Boers did not regard the apprenticeship “inboekstelling” of thousands of “orphan” children as slavery. It was regarded as “charity.”

“In August 1852 Commandant-General MW Pretorius, Commandant PE Scholtz, and Field-Cornet Paul Kruger with 300 sharp shooters, kidnapped 200 children from chief Sechele in the remote area of Bechuanaland and they took the children to Rustenburg, 400 kilometres away. Sechele had done them no harm.

Chief Sechele walked 1 600 kilometres from Bechuanaland to Cape Town to plead with the British Government to get his two sons back. Commandant PE Scholtz later returned his two sons to their tearful mother,” writes Van der Walt.

Van der Walt probably bases this story on the writings of the Scottish missionary and explorer, David Livingstone. Livingstone’s home was ransacked during this attack and the Boers accused him of supplying weapons to the Batswana. Livingstone’s version was vehemently denied by Kruger and others.

The ZAR government gradually started bowing to international pressure, especially from the British empire. In a letter dated 12 January 1857, President MW Pretorius writes to the ZAR’s deputy president, Stephanus Schoeman, urging him to curb the practice of dealing in young slaves. He warns him that “if we want to retain our independence” the ZAR needs to control the traffic of young black children.

Whether Schoeman heeded this call is doubtful. A year later, Rev PDM Huet of the Gereformeerde Kerk (Reformed Church) visited the town of Schoemansdal. In his book “Het lot der Zwarten in Transvaal” he tells how children were being captured in the Zoutpansberg. He describes the brutality of the wars between native tribes and writes: “Maar het is voor mij meer dan waarschijnlijk, dat niet zelden zulke onderlingen … oorlogen plaats grijpen met geen ander doel dan om de kinderen tot buit te maken, ten einde ze te kunnen verkoopen.” (I am convinced that often such native wars occur with no other reason than to capture children and sell them.)

In a letter dated 6 January 1862, the husband of Deborah Retief (daughter of the Voortrekker leader Piet Retief), writes to Stephanus Schoeman: “As u in Zoutpansberg kom, koop vir my vrou ‘n kleyn myt. Moet nie meer as sewe pond (twee beeste) betaal nie want hulle is so volop soos vlieē.” (If you arrive in Zoutpansberg, buy ‘n young black girl for my wife. Don’t pay more than seven pounds, because they are as common as flies.)

President MW Pretorius also booked in “swart ivoor” and he received children as “gifts” from tribal leaders. The amaSwati donated many kidnapped children as political gifts to the Boers. On 12 May 1865 the Landdrost of Lydenburg entered the following in his daily journal: “I, the undersigned, declare hereby that … chief Umzwaas has sent three … orphaned children for the Honourable President MW Pretorius, his ally.” The girls were estimated to be ten years old and the boy eight, these orphans being named Lea, Sara and Jaantje.

“He gave in return two white blankets.”

It is often difficult to distinguish between who were considered to be “refugees” and what was outright slavery. There was the reality of having to deal with orphans and displaced people, especially in a time of turmoil. From what could be established, the children were mostly treated well by the families they were placed at. Still, they had very few rights and had to stay with the family until the age of 21 (and often longer). There were many reports of abuses and it is also clear that the practice of “selling” people was severely criticized by leaders of the predominant churches. It did, however, continue until the 1870s.

In the winter of 1865, the Reverend Charles Murray, an inspector of the Dutch Reformed Church, came across the wagon of a certain Gert Duvenhage in Makapanspoort. Murray wrote:

“Duvenhage had a strange cargo that he was going to trade. In the back of the wagon I saw eight small African children packed tightly together, in the same manner that I, as a child, was wont to observe in drawings of slave ships.” It quickly became clear to Murray that he was dealing with a dealer in "black ivory" and that the children were exposed to severe abuse. Duvenhage was willing to trade the children for six head of cattle.

“When the man spoke to me about the journey, I became extremely angry and told him that his trading practice was one of the reasons why the Lord held back his blessing on the land; it was enough to bring a curse on the Republic,” wrote Murray.

During October 1867, three months after the Vhavenda had torched Schoemansdal, Stephanus Schoeman and his 43 volunteers from the Pretoria Rifle Corps, plus 241 black allies under chief August Zebediela, attacked the female chief Modjadji to extract tribute from her by force.

The Volunteer Commando killed 16 adults and they captured 74 children. They later returned 19 children, aged three years and younger, to their mothers. All in all, 55 children were distributed among the volunteers from Pretoria.

One of the Zoutpansberg residents whose name was frequently mentioned in the “inboekeling” system, was that of Commandant FH Geyser.

The offences were brought to the attention of the ZAR in many cases and court cases and hearings followed. In one such case, the ZAR High Court charged FH Geyser, SM Venter and Joao Albasini with “illegal actions and child stealing”. They were later discharged on a technicality.

Albasini may have continued with this trade for quite some time. On 17 July 1870, Dr BG Arnoldi, a medical doctor from Pretoria, complained in a letter to Joao Albasini that two of his apprenticed girls, Kaatje and Dammio, had found their way back to Zoutpansberg. Dr Arnoldi demanded four heifers as compensation for the loss of the two little girls.

Perhaps the true extent of what had happened is best described by one of the victims, a girl simply known as Adela, who had been captured in the Zoutpansberg in 1865. In an affidavit she described her ordeal:

“The country in which we lived before our people were scattered by the Dutch is near Zoutpansberg. I remember when I was taken, although very young at the time. There were others taken besides myself, some older, some younger.

The Dutch surrounded our kraal while it was yet day, and set fire to the huts. The noise of the fire awoke us, and we ran out just as we were. The grown-up people who attempted to run out of the kraal were shot down, and the rest huddled together, surrounded by the Dutch on horseback.

The children were then put together in one place, while the rest were made to go into the cattle kraal, which was built of stone, and were there shot at till they fell down dead and dying. The Dutch then took us to their wagons, and we were divided amongst them.

I fell to the lot of Mr van Zweel. My master often lived in town, and while there I used to see children brought down from Zoutpansberg and sold for money or cattle. They did not use to hawk children about in the same way when I was taken: this practice has taken place since, but one would sell to another, as occasion required.

When I was about fourteen years of age my master sold me to a Natal … wagon-driver for thirty pounds. I came down here with him, and have lived with him ever since. He was at that time, and still is, wagon-driver to Messrs Barrett of this city.”

And so, after a very long detour, the story returns to the protagonist, President MW Pretorius, who clearly lived in a time of turmoil and change. It was a time of exploration and a time where value systems changed. He was born in a period where slave trading was part of the economy, but he died when the last traces of it started disappearing from the continent. He compiled the ZAR’s constitution, which, among others, states in Art 10: “Het volk wil geen slavenhandel, noch slavernij in deze Republiek dulden.” (The nation will not tolerate any slave trading or slavery in the Republic.)

Interestingly enough, the same constitution also guaranteed press freedom.

* Boeyens, J.C.A. Die konflik tussen die Venda en die Blankes in Transvaal, 1864-1869, 1990

* Ferreira, O.J.O, Montanha in Zoutpansberg, 2002

* Huet, P, Het Lot der Swarten in Transvaal, 1869.

* Van der Walt, J.C, Zululand True Stories, 1780 – 1978, 2007 (as well as numerous articles compiled by Van der Walt for newspapers and other publications).

-

14. The meeting place of opposing ideologies

22 December 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

13. JC Krogh – The maker of peace?

28 October 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

12. Tracing the origins of the first Indian traders in the Soutpansberg

30 September 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

11. The (secret) story that started with Piet Retief

01 August 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

10. The times were a’changin for a controversial president

20 June 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

-

8. The casualties of war for the souls of the Soutpansberg

18 April 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

7. Bvekenya Barnard - the most famous of Crook’s Corner’s elephant hunters

21 March 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

6. The Englishman who helped shape the course of the country’s laws

29 February 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

5. Piet de Vaal, the stately “baobab” of the Soutpansberg

15 February 2016 By Anton van Zyl

ADVERTISEMENT