13. JC Krogh – The maker of peace?

Date: 28 October 2016 Viewed: 23138

Sooner or later we had to get to Krogh Street, which is, after all, the “main” street in town. It used to be the route to the north, leading through Louis Trichardt and passing the important shops, the banks and the post office.

Whether Johannes Christoffel Krogh ever visited the town is not certain, but it is very likely. At one stage in his career (in 1904) he was the magistrate for the Waterberg district and he also had several family ties with local Boer families.

A photo of Krogh Street taken in the early 1900s. (Photo courtesy of Pétria de Vaal-Senekal.)

JC Krogh’s most notable achievement, as far as historians are concerned, is that he was one of the signatories to the Vereeniging Peace Treaty that marked the end of the Anglo Boer War in 1902. Along with Louis Botha, FW Reitz, JH de la Rey, SW Burger and LJ Meyer, he represented the ZAR during the negotiations.

The Krogh family is of Danish origin and first arrived on local shores in 1794 when a young surgeon, Johannes Christoffel Krogh, accompanied his uncle, Dr Zoomers, on a trip to southern Africa. He seemed to have liked the new country and in 1803 married Hester, the daughter of Petrus Ignatius Maré. This was also a quick introduction to the Voortrekker leaders, as his wife’s uncle was married to Johanna Magdalena Pretorius, sister of the well-known Commandant-General Andries Pretorius.

The subject of our story, Johannes Christoffel (jr), was born on 6 September 1846 in Somerset East. He went to school in Uitenhage and later studied at the South African College in Cape Town. When he was only 23 years old he moved to the newly established town of Pretoria to start his career in the government services as a clerk. Four years later, in 1873, he married Maria Meintjies.

In March 1877, the then president of the ZAR, TF Burgers, appointed him as public prosecutor for the Pretoria district. In the same year, T Shepstone marched into Pretoria to annex it for the British government. In August 1877, the “Secretary to the Government”, Mr M Osborn, writes a letter to Krogh to “appoint you, without salary, to act as Registrar of the HIGH Court of Pretoria during the absence of Mr. Haggard on Circuit.”

Krogh became magistrate in the Pretoria court in May 1878, following the resignation of William Skinner. He served in this position for more than three years, before being appointed magistrate of Wakkerstroom in August 1881. He stayed in this district for almost 14 years, after which he was appointed as the “Special Commissaris” (Special Commissioner) of Swaziland. One of his first tasks was to help demarcate the border between the ZAR and Swaziland. The beacon north of the Mbuluzi River is still called “Krogh’s Beacon”.

When the Anglo Boer War broke out in 1899, his knowledge of the country, especially Swaziland and the adjacent areas, became very useful. On 23 August 1901, while still in the field, JC Krogh was elected to the executive council of the ZAR. It was also in this capacity that he participated in the negotiations to end the three-year-long war. Interestingly enough his signature on the peace treaty had the title “Vrederegter der ZAR” (Peace Officer of the ZAR) below it.

Two members of the ZAR Executive Committee (Cabinet) of the ZAR government, General Lukas Meyer and Mr JC Krogh (right) accompanied by the secretary of the Government, D van Velden, visited Pilgrim’s Rest during May 1902 to inform the burghers of the peace process and to elect representatives for the discussions at Vereeniging. (Photo is from an article: VELDPOND: THE TRUE FACTS. PILGRIM’S REST 1902. The researcher is Dr Rentia Landman)

After the war, Krogh was appointed as magistrate in Lichtenburg and in 1904 he became magistrate in the Waterberg district. When the Union of South Africa was formed in 1910, Krogh became a senator and moved to Cape Town. He died on May 5, 1921.

The story of Krogh may have ended here, but that’s not the way life works. People often “live on” through the legacy of their children, and in this case perhaps the grandchildren. JC Krogh had a very interesting grandson, who helped shaped the future of a young democracy some decades later.

JC Krogh’s daughter, Elizabeth, married an attorney, James Louis Steyn Berrangé, and they had a son, Vernon Celliers Berrangé, who was born during the Anglo Boer War, on 25 November 1900. This son of theirs was later described as the “defender of the people” and in 2010 posthumously received The Order of the Companions of OR Tambo in Silver.

The young Berrangé was described as someone with “a penchant for high living and fast cars. He was always against authority, loved a challenge and revelled in danger.” After a short stint in the Royal Air Force, he returned to South Africa and studied law. He graduated in 1924 from the University of Cape Town with a BA LLB degree. He was admitted to the South African Bar in 1924, but in 1926 he left the Bar and went into partnership with his father.

Berrangé built up a reputation as an outstanding criminal defence and human rights lawyer with a reputation for devastating cross-examination. He was also a co-founder of The Organisation for Rights and Justice and chairman of the Legal Aid Society. He was known for his willingness to accept briefs in cases where non-whites were charged under the discriminatory apartheid laws. In many of these cases he acted pro bono.

Berrangé joined the SA Communist Party in 1938, believing that this organisation shared his ideals of a more just society. When the SACP was dissolved in 1950, after the Suppression of Communism Act was promulgated, he resigned from the party. He also became disillusioned with the communist ideology, believing that it no longer served the interests of the people.

In a statement filed in 1962, Berrangé explained his decision to leave the SACP. This statement formed part of an application to have his name removed from the Liquidator’s list of named communists.

“My sympathies lie with all organizations that endeavour to establish in this country my concept of democracy. That, in my view, embraces bodies that strive to ensure for all citizens of the country freedom of thought and speech and the right of assembly. It also includes bodies that seek to attain for all citizens, irrespective of their colour or race, equality of opportunity and the right of participation in government: such bodies that hold all persons are entitled to equal educational and social facilities, to the right to move freely and to compete equally on the labour market, and to live and work where they so desire. It includes bodies that are opposed to, and desire to change, the laws that deny these rights to the citizens of this country and to the laws that make it permissible for persons to be imprisoned, banished or penalised, without being brought to trial and without being given the right to answer in our Courts the allegations made against them.”

Despite this change of political views, he remained friends with some of his former comrades, such as Bram Fischer, and defended him in court. He also became more and more involved in high-profile political cases, such as the Alexandra bus boycott, the African mine workers’ strike and the Alexander Libel Trial.

The Treason Trial of the late 1950s caused Berrangé to become a household name among certain sectors of the community. The Nationalist Party government arrested 156 people and charged them with high treason. The names of the accused included those of Oliver Tambo, Nelson Mandela, Chief Albert Luthuli and Helen Joseph. In March 1961, more than four years after the trial had started, the court found all the accused not guilty. Berrangé was carried aloft outside the court.

Much has been said and written about Berrangé’s contribution to the political struggle in South Africa. When the Rivonia Trial started in 1963, he was alongside Bram Fischer in court. Berrangé’s story is, however, not really one for this series. (Unless someone decides to name a street in town after him.) He died on 14 September 1983 in Swaziland.

We now need to return to the street itself.

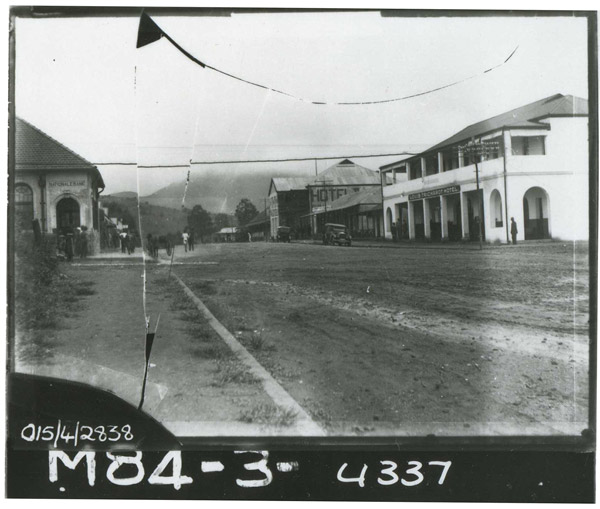

Photo left: A photo taken, probably in around 1920, of the Krogh and Trichardt street interchange. The National Bank building is on the left and Hotel Louis on the right. (Photo courtesy Hugh Exton Museum: Polokwane)

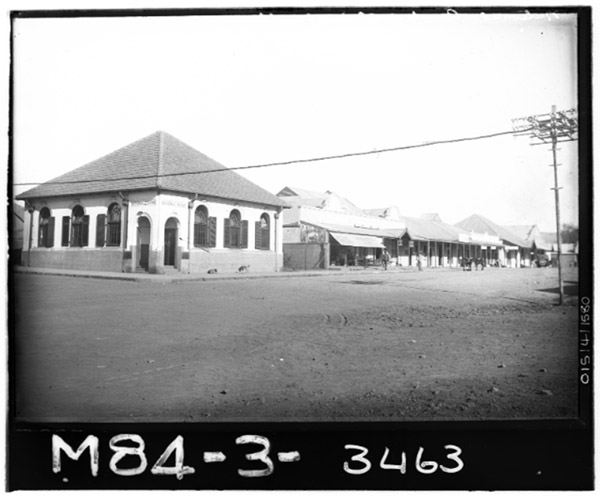

Photo right: A photo taken in around 1915 of the Krogh and Trichardt street crossing.(Photo courtesy Hugh Exton Museum: Polokwane)

Krogh Street was literally the centre of activities in town for many decades. The first school building, albeit a tin shanty, was on the corner of Krogh and Erasmus Street. The first municipal building, completed in 1922, was in Krogh Street. This building later hosted the town’s first library. Even the first “hospital” was in Krogh Street. In 1923, the village council gave permission to Dr S Kirk-Cohen to use his house in Krogh Street (“opposite the old fig tree”) as a hospital for the town.

The street played host to a great number of general dealers, the first banks, motor dealers such as General Garage and hardware stores such as Economic Cash Store. The first Indian traders, such as Dungarshi Morarjee and the Surat family, also had stores in Krogh Street. The street also hosted the most popular bars in the district, probably none more famous than Hotel Louis on the corner of Krogh and (then) Trichardt Street. According to Johann Tempelhoff’s book on the town’s history: “In 1920 the Hotel Louis was occupied by Mr. E. Titmous and owned by Mr. A. Abramowitz. The nearby Zoutpansberg Hotel was owned and occupied by Messrs. Lewis and Goldman.” For a quick snack, the Great North Café was a favourite.

Apart from the hotels, bars, grocery stores, banks, hardware stores and motor dealers, the street also attracted the religious fraternities. The prominent Church of the Vow (Dutch Reformed Church) was built on a site bordering Krogh Street. (This land was later subdivided and the modern Standard Bank building now faces Krogh Street). The first church building of the St Marks Anglican Church was in Krogh Street, but moved in 1969 after a new church was built in Munnik Street. Part of the stone doorway of the original church was reconstructed adjacent to the new building in memory of the original church. Even the Jewish residents favoured the street, but had to wait until after World War II for a synagogue to be built. In 1957, the local Nederduitsche Hervormde congregation acquired a piece of land in Krogh Street to build a church. At that stage the congregation had roughly 500 members.

Krogh Street was also the venue for the first show. Nobody seems to remember precisely when the first show was held, but it was probably in the early 1950s. A resident, Mr Sybrand Mostert, recalled many years later that the show lasted only one day. This show later became an annual event, held over three days.

As would be expected from a popular street, it hosted the odd “fight” now and then. One such skirmish was in August 1951 when residents (and the traffic chief) started complaining about the trading activities at the site where the Saturday morning markets were held. This was apparently fuelled by a local farmer who had started selling fish and fresh produce, such as vegetables and eggs, at the site. Other farmers followed suit and the town council had to step in to restore order (and protect the other businesses and traders who annually paid for trading licences). The activities also posed a threat for the traffic passing by. A committee was established to investigate and make a recommendation. Three years later it was recommended that no fresh produce sales be conducted in Krogh Street between Devenish in the north, Erasmus Street in the south, Burger Street in the East and Munnik Street in the West.

In the mid-1900s, Krogh Street formed part of the national road heading to the north. In May 1952, the town council was informed by officials of the National Roads Board (NRB) that the town would not be bypassed when the new national road was to be constructed. At the time, plans were set in motion to construct a new bridge in town on the Pietersburg road, and also the Messina Bridge was to be widened. In March 1954, it was disclosed that both Rissik and Krogh Street were to be reconstructed and tarred by the NRB, as they formed part of the national road. The NRB also offered to tar the streets of Louis Trichardt joining up with the national road at a cost of £15 000.

In the mid-1970s, the street lost its status as “national road” when the new road bypassing the centre of town, the current N1,was constructed.

A very early (undated) picture of Krogh Street, heading towards the mountain. (Photo courtesy of Pétria de Vaal-Senekal.)

Finally, to pay a last tribute to Krogh Street, it also hosts the town’s only “skyscraper”. In 1989 the Pennells Group of Companies commissioned the R2,8 million Pennells Centre on the corner of Krogh and Magistrates Avenue. This six-storey building boasts the first (and only) illuminated exterior elevator in Louis Trichardt.

Sources:

* Tempelhoff, Johann W.N., Townspeople of the Soutpansberg – A centenary history of Louis Trichardt (1899-1999), 1999.

* Punt, W., Pretoriana, Vol 2 No 3, April 1953, “’n Versameling Seldsame Dokumente en Foto’s”. 1953.

* Landman, Rentia, Veldpond: The True Facts. Pilgrim’s Rest 1902, 2010 (revised).

* SA History Online: http://www.sahistory.org.za/people/vernon-celliers-berrange

-

14. The meeting place of opposing ideologies

22 December 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

13. JC Krogh – The maker of peace?

28 October 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

12. Tracing the origins of the first Indian traders in the Soutpansberg

30 September 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

11. The (secret) story that started with Piet Retief

01 August 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

10. The times were a’changin for a controversial president

20 June 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

-

8. The casualties of war for the souls of the Soutpansberg

18 April 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

7. Bvekenya Barnard - the most famous of Crook’s Corner’s elephant hunters

21 March 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

6. The Englishman who helped shape the course of the country’s laws

29 February 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

5. Piet de Vaal, the stately “baobab” of the Soutpansberg

15 February 2016 By Anton van Zyl

ADVERTISEMENT