2. The senator who preferred ‘velskoene’

Date: 18 December 2015 Viewed: 23454

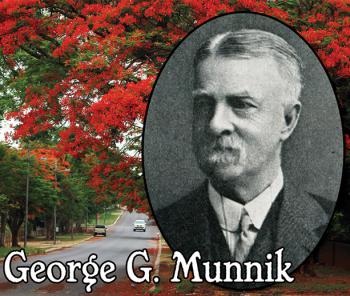

George Glaeser Munnik left his mark on the Zoutpansberg in many ways, but probably more so because he bothered to write it down. This former magistrate and senator of the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek captured the history of the region (as well as his own) in several books that he wrote.

He was born in Worcester, in what is now called the Western Cape, on 26 April 1846. His parents were prominent people in the Cape Colony and his father, John Hendrick Munnik, held the title of notary public to the Colony. His mother was a daughter of Dr George Glaeser, the district surgeon of Worcester.

The young Munnik started his career as Resident Magistrate’s Clerk in Graaff-Reinett. He did duty in places such as Barkley East (1880), Barberton and Klerksdorp. The then president of the Transvaal Republic, Paul Kruger, heard about Munnik and offered him a position as Acting Landdrost of Pretoria.

One of the delightful stories told by Munnik in his memoirs concerns the duties that the landdrost had to perform in the early years of the ZAR. The Volksraad took a decision that a marriage could only be performed by the landdrost of the district. This of course meant that families had to travel from afar to legitimise the union of the young men and women.

On one such day, the “vierperdewa” drawn by four grey horses and escorted by about a dozen armed and mounted burghers drew up at a Landdrost’s office in the far north. The pretty groom and bride, along with the family members and friends, arranged themselves around the “rostrum” of the Landdrost. The worthy official performed the ceremony and said to the bridegroom, “The fee is £3, give it to me.” “I have not got it,” stammered the unfortunate bridegroom, “and was going to ask you to let me pay at the end of the month.” “What!” roared the Landdrost, “you are defrauding the revenue.” He then ordered one of the constables to lock up the bride in his private office until such time as the groom produced the £3.

“This did not suit the old landdrost’s wife, and the idea that her husband had a pretty girl locked up in his private room rankled in her soul, so she went to her husband’s ‘wa-kist’ where he kept his private money, got out £3 and, going to the back window of the office, called the pretty bride and, giving her the money, said, ‘Knock at the door and give this to your husband to pay the marriage fee,’” writes Munnik.

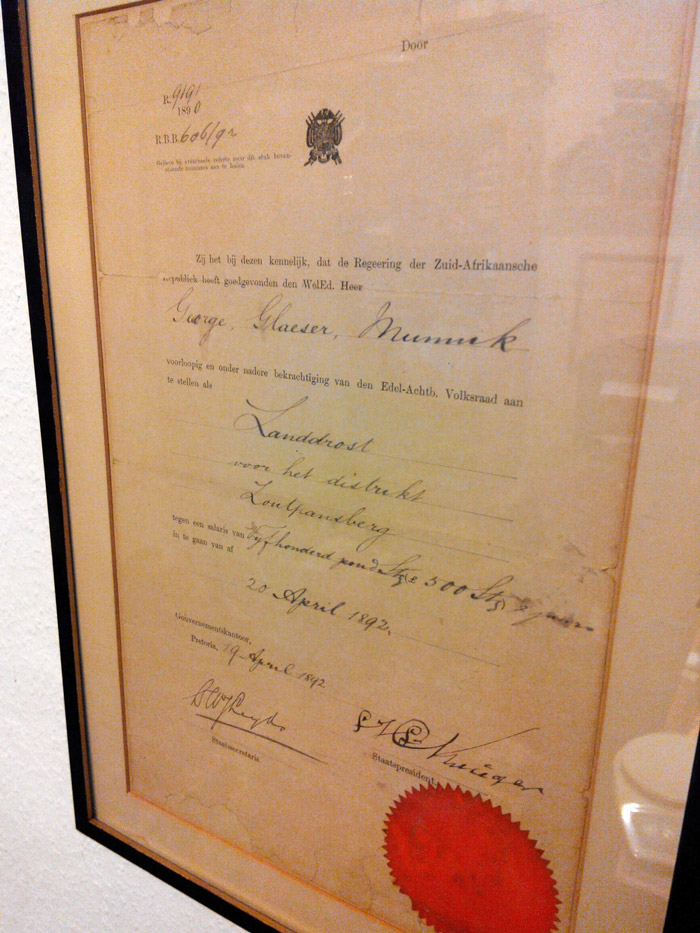

The original Landdrost employment contract for GG Munnik in the Zoutpansberg, dated 19 April 1892 and signed by President Kruger. (Picture provided by Mr CH Perkins)

But back to the acting landdrost Munnik. After about three months in this position, he was summoned by President Kruger to appear in his office. The President quickly informed him that John Rabie, the Mining Commissioner of the Zoutpansberg, had died of pneumonia during the night and he wanted Munnik to replace him. Munnik was not given much of an option in this matter and the next day he was on a coach heading for Smitsdorp (close to where the current Polokwane is).

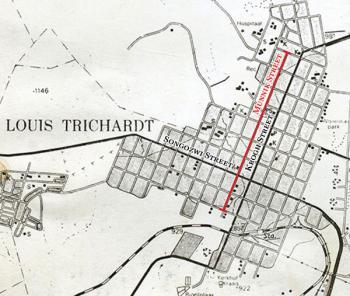

Munnik has left many marks in the region and these are not limited to place and street names. Not long after he had arrived in Smitsdorp, he teamed up with a Mr T Kleinenberg and they started the Zoutpansberg Review newspaper. This paper survives to this day, albeit that it nowadays is known as the Northern Review.

Following Landdrost Maré’s death (also of pneumonia), the vacant position in Pietersburg had to be filled and, much against Munnik’s wishes, he had to move into this position. It seemed as if the then Smitsdorp opted to move with Munnik and a few months later, this mining town was no more as all activities such as banking made the move to Pietersburg.

Munnik had a fair amount of respect for the leaders of the various tribes, and had this to write about his encounters with Makhado (or Magato as he referred to him). “When Magato arrived at manhood and got rid of Katlachter’s tutelage, he proved himself to be a proud native aristocrat who ruled his tribe with an iron rod, but fairly. As Landdrost of Zoutpansberg I often came into contact with him, and although he silently ignored the Republic’s authority, he never openly defied it.” Makhado, known as the “Lion of the North”, called Munnik “Inkose Pulakwan”.

In a strange anomaly in the laws of the Republic, the commandant of the district did not fall under the jurisdiction of the landdrost, but directly under the Commandant-General in Pretoria. This caused a fair amount of conflict, and almost led to a declaration of war against Makhado. When Munnik heard that Swart Barend Vorster (Moekoentaidie) was raising a commando to punish Makhado for “some imaginary grievance” (as Munnik states), he quickly mounted a buggy and went off to the north to investigate.

Munnik gives a very colourful description of how he and his wife set off at three that morning and first travelled the 60 odd miles to John Cooksley’s place. They arrived before noon and asked a trooper, Terry Fitzgerald, to ride through to Makhado’s kraal and make an appointment for the next morning at ten.

Munnik and his wife, joined by Mr Cooksley and his wife, set off early the next morning to the spot where the meeting with Makhado was to take place. When they arrived, Makhado was already there, well dressed as usual. After the customary greetings, about 1 000 armed warriors appeared. Mrs Cooksley, who knew Makhado well, asked him about the reasons for the warriors. “I did not call them, but they love me so much and are so afraid that you will kidnap me, that they came of their own accord to protect me,” he answered.

Munnik then asked about the reason for the war against Tshivhase. Makhado vehemently denied this and pointed to his “generals” who were present. “If I was fighting a chief like Tshivhase, just as strong as I am, do you think they would be here this morning?” he asked.

Makhado was clearly upset with Moekoentaidie’s intention to assist Tshivhase and when he was told that it was also because Tshivhase pays taxes, he replied “Tshivhase is a liar. He sends you £500 every now and then when he ought to send you thousands. I am honest to say I will pay no taxes, and you were coming to help this liar!”

Munnik succeeded in persuading Commandant Vorster not to go ahead with the plans to attack Makhado and disband the commando. A fairly cordial relationship existed between the Republic and Makhado, but the same could not be said for Makhado’s predecessor, Mphephu.

Munnik was an active campaigner in the Anglo Boer War that broke out in 1899 and, as officer, took part in several skirmishes with the British. He was captured near Zebediela and subsequently sent to a prisoner-of-war camp in Trichinopoly, India. When he was eventually sent back to South Africa, following the peace treaty, he bought property near Pietersburg where he farmed for a few years.

Before the general election of the first parliament for the Union of South Africa in 1910, the Zoutpansberg district was divided into two, an east and a west side. Munnik at that time had already became involved with politics and was instrumental in the formation of the “Het Volk” political party (which later merged into the National Party). He managed to beat Dr George Hay, a medical doctor from Louis Trichardt, during the elections by nearly four hundred votes. That started a career of over 30 years as Member of Parliament. He was also selected to serve on the Senate for three terms.

The interesting “Senator” or “Landdrost” Munnik left deep footsteps in the Soutpansberg region (and more literally with his “velskoene”, because he preferred these to imported boots). He died in 1935 at the age of 89.

His legacy, however, is not lost to the region. His daughter, Maud, married into the Kleinenberg family which still has several descendants living in the region, among them the Leach and Adendorff families.

Sources:

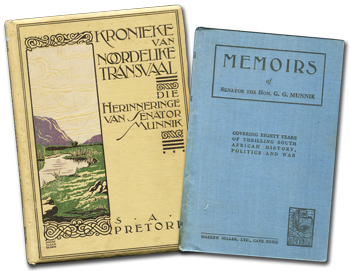

Senator G.G. Munnik: Kronieke van Noordelike Transvaal

Memoirs of Senator the Hon. G.G. Munnik

-

14. The meeting place of opposing ideologies

22 December 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

13. JC Krogh – The maker of peace?

28 October 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

12. Tracing the origins of the first Indian traders in the Soutpansberg

30 September 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

11. The (secret) story that started with Piet Retief

01 August 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

10. The times were a’changin for a controversial president

20 June 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

-

8. The casualties of war for the souls of the Soutpansberg

18 April 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

7. Bvekenya Barnard - the most famous of Crook’s Corner’s elephant hunters

21 March 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

6. The Englishman who helped shape the course of the country’s laws

29 February 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

5. Piet de Vaal, the stately “baobab” of the Soutpansberg

15 February 2016 By Anton van Zyl

ADVERTISEMENT