9. Could a future king of the Bavenda have grown up in the house of a ZAR president?

Date: 23 May 2016 Viewed: 22154

This week’s story starts with a general, moves to a president and then pays a visit to two kings. As usual the focus is on the events in history that made the Soutpansberg such a unique place.

History is often controversial and people tend to disagree on the factual presentation thereof. For this reason a lot of publications prefer to avoid the conflict and focus on the less “problematic” news. We thought about that route and decided against it. (Would you have expected anything else?) The reality is that none of us can change the history. We can only learn from history. (Although George Bernard Shaw is quoted as saying “We learn from history that we learn nothing from history.”) And if nothing else, it always makes for interesting reading, especially if there is a mystery surrounding it.

The challenge in this series is often to find the “local angle” in the street names of our town. It is a series about the history of the Soutpansberg and its people, which also means that we’re less interested in people who have never been here or who did not play a significant role in the development of the area. Some streets, however, were named after people who have never even set foot in the region.

When Burger Street was mentioned, the fear was that this would be a difficult street to feature. The first problem was to establish who exactly the street had been named after. It is also not as though there are detailed minutes available from the late 1800s that explain the rationale for naming the streets. One gets the impression that the naming of streets was done on the spur of the moment and left up to the land surveyors and cartographers.

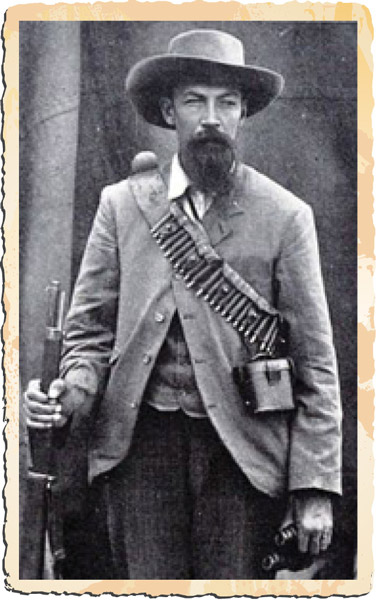

The first guess was that Burger Street had been named after the famous General Schalk Burger (top picture). He was born in 1852 in the Lydenburg district and was well known in political circles. He served as a member of the “Volksraad” of the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republic, and in 1898 he even stood against Paul Kruger for president. He lost this election, but less than a year later he was promoted to general and took part in the Anglo Boer War.

When Commandant-General Piet Joubert died in March 1900, Burger became vice-president and later acted as president when Paul Kruger visited Europe. General Schalk Burger was one of the signatories to the Vereeniging peace treaty that marked the end of the Boer War.

If we were less inquisitive, this would probably have been it (and this week’s contribution would be have been short), but this was not to be. When looking a bit closer at the original town map, compiled by HM Anderson in December 1898 and January 1899, a few interesting aspects stand out. The original map spells the name of the street as Burgers Street. It is possible that the street name was simply misspelt (Kruger Street is also spelled as Krugers Street), but there seems to be a pattern. The three streets, President, Kruger and Burgers, run parallel to each other, which may indicate a theme. Could the street perhaps have been named after one of the most controversial presidents of the ZAR, TF Burgers?

Thomas Francois Burger was born in the Graaff-Reinet district on 15 April 1834. After finishing school, he travelled to Utrecht in the Netherlands to study theology. It was also while abroad that he started adding an “s” to his surname. He married a Scottish lady, Mary Bryson, and out of this marriage 10 children were born. In 1859 he accepted a post as reverend in the Dutch Reformed congregation of Hanover in the Karoo.

Early in his career, Burgers had to become used to controversy and criticism. In August 1862, an elder of a neighbouring congregation complained to the church authorities that Rev Burgers was heard teaching a false doctrine. Among the things that Burgers is alleged to have said, was that there was no description in the Bible of the devil. Burgers apparently stated that nowhere was it mentioned that the devil had a tail. Burgers was also accused of having said that Jesus, during his life on earth, had human traits. Jesus would, for example, be hungry, thirsty and afraid and would have had a sinful human nature.

This charge, however, marked the start of a long battle that eventually had to be decided by the courts. After being found guilty by the Dutch Reformed Church, Burgers took the matter to the High Court, arguing that the church had never followed its own rules. The High Court ruled in his favour and ordered the church to pay the costs of the case. The church then took the matter to the Privy Council in London, asking this body to set the verdict aside. In February 1867, the Privy Council ruled against the Dutch Reformed Church. The church leaders were still not satisfied and wanted to petition the Queen of England to intervene. After being told by two senior advocates in London that they had almost no chance of success with this appeal, the church eventually backed down, and in October 1870 Burgers was allowed to preach again.

It was, however, clear that Burgers’s more enlightened view on theology would not go down well with all members of the Dutch Reformed Church. In a strange twist of fate, he was dragged into politics and less than two years later, in July 1872, he became the president of the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republic. He was then only 38 years old.

Much can be said for the manner in which Burgers became president, but space in this article does not allow for it. Suffice to say that he arrived on the scene when the “old” leaders had left (hurriedly) and the new ones had not yet established themselves. New blood was needed and the republic needed someone strong to try and sort out the mess that president MW Pretorius left behind when he resigned. The country was in dire financial straits and the armed forces had to deal with several wars that were brewing. The ideal candidates for the position of president, such as President Brand from the Free State, did not want the job.

At this stage we must pause and ask what all this meant for the people of the Soutpansberg? Is there any local angle to the history of Pres TF Burgers? Well, there may be, but from a completely different angle.

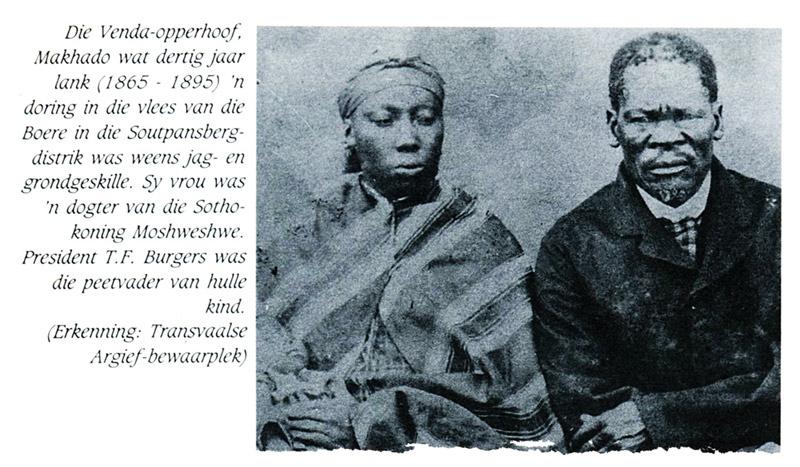

In the book of Dr Uys de Villiers Pienaar, Neem uit die Verlede, a photo appears of the Venda king, Makhado. In the photo (as seen below), Makhado poses with his wife, described as the daughter of the Basotho king, Moshoeshoe. Interestingly enough the caption further states that the godfather of their child was Pres TF Burgers.

To add a bit of spice to the mystery, a very interesting picture appears in the biography of TF Burgers, written by PS Engelbrecht. In this book, Burgers is photographed on the porch of his farm house along with his wife and daughters. The caption merely states “President Burgers with his family on the stoep.” Right in the middle of the photo sits a neatly dressed black boy, complete with traditional shirt.

Could it be that the ZAR president took in the son of a Venda king and raised him as his own?

To answer this question, one probably has to look at it from a variety of angles. A starting point would be the documents and writings left behind by Burgers. A highly respected US historian, Prof Lindsay Braun, could not find any direct evidence of such a son in the Burgers household. Even Jan van der Merwe, a South African historian who wrote several pieces on the history of Burgers, could not shed more light on the matter. Both could confirm that Burgers was very liberal in his thinking and an enigma in his time.

When Burgers became president of the ZAR in 1872, he was not accepted with open arms. Paul Kruger, Piet Joubert and DJ Erasmus were very much against his appointment. He was under enormous pressure from Lord Carnarvon, the British minister of colonies, to incorporate the Transvaal into the rest of the British colonies. The international community also pressurized the ZAR to take stronger action against practices described as disguised slavery.

When Burgers took up office, he inherited the highly controversial pass law, pushed through during DJ Erasmus’s brief reign. This law prescribed that every black resident of the ZAR, with the exception of traditional leaders, women and children, had to purchase a pass from the local “landdrost” or “veldkornet” at a cost of £1. The law, which became effective on 1 January 1873, also meant that black residents with a pass would be regarded as citizens of the state.

The pass laws were not popular and it quickly became clear that the implementation of such a system would be doomed to failure. Burgers, with his more liberal views, found himself more and more isolated. It is interesting to note that, in the mid-1870s, Burgers suggested a system whereby black residents of the country who showed a willingness to work, should be awarded full citizen's rights and have the opportunity to own land.

The time was, however, not right for such drastic steps and at the end of Burgers’s term as president, no law had been passed whereby black people could obtain land in the ZAR.

However, we have to move back to the Soutpansberg and explore some other angles to judge whether or not it was possible for Burgers to be the godfather of a Venda child.

The marriage between Makhado and the daughter of Moshoeshoe is not unlikely. Makhado was born in 1825 and reigned from around 1865 until his death in 1895. King Moshoeshoe lived from 1786 to 1870. A daughter of Moshoeshoe would thus have been in the age group for Makhado to marry.

When Moshoeshoe was still a young boy (and apparently quite a “rebel”) he was taken to the great African philosopher and diplomat, Mohlomi. Mohlomi travelled across southern Africa, visiting different tribes and forming bonds of friendship. During his earlier years, Mohlomi also visited the Vhavenda. Moeshoeshoe would have learned from this and would also have had contact with his northern neighbours.

The writer, Max du Preez, writes about Moshoeshoe’s manner in which he ruled: “But he had another clever method to assure peace and respect for his authority: he married women from chiefdoms and clans in his region – among them San, Zulu and Xhosa speakers. The chief of a clan whose daughter was married to Moshoeshoe would think twice before attacking him. By the time he was 60, Moshoeshoe had more than 150 wives.”

The practice of allowing a daughter to marry a chief from another tribe would have made diplomatic sense. For Moshoeshoe it would have made sense to also form strong bonds with the ZAR government. Du Preez writes: “He spent the last 40 years of his life using all his diplomatic and negotiating skills to protect his people from being swamped by the Boers, who were mostly supported in their quest for land and sovereignty by British colonial officials from the Cape Colony.”

Whether the child of such a marriage would be sent away to live with a white family is perhaps doubtful. The practice of sending the king’s children to live in far-off villages was, however, not uncommon. This was often done to protect the child from his future enemies.

In the Venda custom, the new heir would not necessarily be the first-born son of themahosi or the first son from a specific wife. The prerogative to choose a successor would be that of the royal family, and more specifically the khosimunene (uncle) andmakhadzi (aunt). This was a secret decision only announced a year after the death of the ruling king.

We do, however, need to return to Pres Burgers and his struggle to transform the ZAR, the government on the brink of bankruptcy that he had “inherited”.

Burgers took a bold step and borrowed some £60 000 from the Cape Commercial Bank to rescue the government’s currency. He also arranged for the first Burger pounds to be minted in Birmingham, England. To upset the old establishment even further, he stopped the payments to members of the commandos because he believed the government could simply not afford this.

One of TF Burgers’s dreams was for the ZAR to have its own railway line, opening up the trade route to the then Delagoa Bay. In 1875 he travelled to Europe to raise money for this ambitious project. He managed to convince the Portuguese government to support the project and on 8 January 1876 the deal was signed whereby the firm Insinger agreed to lend the money to the ZAR to build the railway line.

One aspect where Burgers had failed, was to muster the support of his colleagues. When the war against Sekhukhune broke out in 1876, neither Paul Kruger nor Piet Joubert wanted to help him. They still blamed him for disbanding the commando service. Burgers eventually had to take out mortgages on his farms in the Richmond area to finance this war.

During all this time, the British authorities were searching for excuses to include the Transvaal in their colonies. Burgers was well aware of the fact that Sir Henry Barkley and Lord Carnarvon had definite plans to bring British rule to the ZAR, but his fellow “volksraadslede” did not believe him.

On 22 January 1877, Sir Theophilus Shepstone rode into Pretoria,followed by 25 policemen and eight officials. Their “friendly” visit to discuss certain grievances ended up in what can be described as a hostile take-over. Shepstone argued that the ZAR had become an unstable factor in South Africa. The government was bankrupt, Burgers was not popular and the war-mongering black tribes put everyone at risk, was the message. Burgers objected, but on 12 April 1877 Shepstone officially proclaimed that Transvaal is part of the British empire.

In May 1877, Burgers left Transvaal to settle on an ostrich farm in the Hanover district. In 1879 he moved to a farm he had hired in the Richmond area. On 9 December 1881, after being sick for some time, he died as a relatively poor man in Richmond.

In later years president Paul Kruger did a lot to defend Burgers and seemingly realised the wisdom of his predecessor. “Hij had zijn Land en Volk erg lief, maar was zijn tyd ver vooruit,” he said during a public meeting in Rustenburg in 1898. (He loved his land and nation very much, but he was way ahead of his time.)

As far as the mysterious black son in the family picture is concerned – it most probably is not the son of Makhado. Prof Lindsay Braun, the US writer and historian, reckons the photo in De Villiers Pienaar’s book is not that of the Venda king. He suggests that it is rather a photo of Chief Mokgatle, the Bafokeng leader from the Rustenburg area, who was often referred to as Makgato. “He was a Christian, sent his sons to school abroad, and was quite favoured by Burgers,” writes Braun.

Mokgatle’s visits to Moshoeshoe are well recorded and in 1861 he lived in Lesotho for roughly five years as guest of the Basotho king. The sons, perhaps under influence of Burgers, eventually went to study theology in the Netherlands. Interestingly enough, this visit was made possible by another ZAR president, Paul Kruger. More about Kruger, however, in a next article.

Sources:

Lecture by Jan JP van der Merwe on the history of TF Burgers, based on the biography written by PS Engelbrecht. (http://www.litnet.co.za/thomas-francois-burgers)

U de V Pienaar, Neem uit die Verlede, 1990

Du Preez M, Of Warriors, Lovers, and Prophets: Unusual Stories from South Africa's Past, 2004

Readers with information on the streets not yet covered in the series must please contact Anton at [email protected] or Pétria at [email protected].

-

14. The meeting place of opposing ideologies

22 December 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

13. JC Krogh – The maker of peace?

28 October 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

12. Tracing the origins of the first Indian traders in the Soutpansberg

30 September 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

11. The (secret) story that started with Piet Retief

01 August 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

10. The times were a’changin for a controversial president

20 June 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

-

8. The casualties of war for the souls of the Soutpansberg

18 April 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

7. Bvekenya Barnard - the most famous of Crook’s Corner’s elephant hunters

21 March 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

6. The Englishman who helped shape the course of the country’s laws

29 February 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

5. Piet de Vaal, the stately “baobab” of the Soutpansberg

15 February 2016 By Anton van Zyl

ADVERTISEMENT