8. The casualties of war for the souls of the Soutpansberg

Date: 18 April 2016 Viewed: 20735

The street to be scrutinized this week, is Van Warmelo Street, but as has become the norm in this series, we deviate a bit. A number of readers have pointed out that the articles don’t always focus on the specific person the street was named after. This is true, because it is not a series of biographies – it is a series focussing on the history of the region. The name of the street is a starting point, but from here we explore the rest of the region. Often the exploration ends in areas where the streets have no names, or otherwise put, where the main role players’ names were never put on street signs. The story that starts with Van Warmelo is one such exploration.

In the small graveyard at Schoemansdal, only two graves have tombstones. One is a dedication to the pioneer Voortrekker, Andries Hendrik Potgieter, while the other tombstone pays homage to Josina van Warmelo, wife of the minister of the Nederduitsche Hervormde church, NJ van Warmelo.

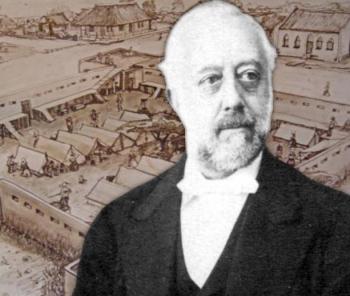

One of the oldest streets in Louis Trichardt is named after Nicolaas Jacobus van Warmelo, the first clergyman to take residence in the town of Schoemansdal, way back in 1864. He only lived here for less than three years, but during this time left quite an impression on the hunters, traders and possibly also slave dealers in this northernmost town of the ZAR.

Van Warmelo was born in Gouda in the Netherlands and was admitted as a minister of the Nederlandse Hervormde church in 1858. The idea of doing missionary work in Africa appealed to him and in 1862 he visited the Cape. He initially assisted in preaching the gospel in Cape Town under the guidance of the Dutch Reformed Church minister JS Spijker. While in Cape Town, he met Rev GW Smits from Rustenburg, who encouraged him to take up the position of minister in the Hervormde church at Schoemansdal.

Van Warmelo first had to return to Rotterdam, among others to get married to Josina van Vollenhoven in February 1864. She was the fifth child of Pieter van Vollenhoven, president of the judiciary in Rotterdam. His parents-in-law were not very keen on letting their daughter explore the unknowns of Africa, but the newlywed couple were determined to go.

Three months after the wedding, the couple arrived in the Transvaal and Rev Van Warmelo was sworn in as a minister of the church in Pretoria. On Friday, 29 July 1864, Rev Van Warmelo attended his first of many church committee meetings in Schoemansdal and the next day some 600 people witnessed his inauguration as first minister of the local congregation of the church. The then president of the ZAR, M.W. Pretorius, and several members of his executive council were also present.

Van Warmelo had an immense passion and love for the people of the Soutpansberg and described them as “mijne eigene gemeente, mijne schaapjes” (my own community, my sheep). Josina found herself in the role as the “mother” of the congregation and had to get used to the somewhat strange customs of the local people. Every Sunday morning a wife of one of the elders in the church would come to fetch her at home and accompany her to her seat next to the wife of the eldest “ouderling”. It was quite a shock when Josina died after a short illness on 28 January 1865 and Van Warmelo was very depressed for some time.

Van Warmelo was not the first man of the cloth to bury his wife at the foot of the Soutpansberg mountain range. On 25 June 1862 a Scottish reverend, Alexander MacKidd, married the 36-year-old Boer lady, Ester Susanna (Hessie) Bosman. The marriage ceremony was performed in Bloemfontein by the well-known reverend of the Dutch Reformed Church, Andrew Murray. MacKidd was recruited in Scotland, as the Cape-based church could not find a local reverend willing to enter the missionary fields.

To be a missionary during the 19th century was also no easy task. The ZAR government was not very accommodating and did not trust missionaries. It was against the law to teach the gospel to black or coloured people and special permission from the local magistrate was needed for this. MacKidd therefore had to wait before he could venture further north to hunt for the souls of the indigenous people.

His opportunity eventually came in December 1862 when the Buys community from the Soutpansberg invited him to come and stay among them and teach the gospel. The letter inviting him was signed by Michael Buys, one of the sons of the legendary Coenraad de Buys. De Buys and his family arrived in the Soutpansberg in the early 1820s. He disappeared without a trace in 1829, leaving behind his family on the banks of the Limpopo river.

The MacKidd couple left for the Soutpansberg on 25 April 1863. They arrived on the farm of the Lottering family on 13 May 1863 and the young reverend delivered his first sermon four days later. This also caused the first of many conflicts within the local white community, as he baptised two white children. This did not go down well in a community where most of the residents were members of the Hervormde church. Members of the Dutch Reformed Church (NG Kerk) and the Hervormde church did not agree on a number of matters (to put it lightly).

MacKidd initially started with his work on the farm Goedgedacht, which was donated to the church by Lottering. He soon realised that more space would be needed and bought the farm Kranspoort, using his own money. This would become the base from where the missionary work was to be done. (MacKidd also stated in his will that this farm was to go to the church after his death to be used for missionary work). Not only Rev MacKidd made an impression with his earnest dedication. His wife very quickly started teaching lessons for young and old. When the first buildings arose at the missionary station at Goedgedacht, the lessons became more structured, and in the evenings Hessie MacKidd could be found singing and praying with a group of children.

The Soutpansberg was notorious for its “deadliness” and in April 1864 Mrs Hessie MacKidd went down with the fever. She died on 4 May and probably became the first white person to die while on a missionary station in the Soutpansberg. Her husband followed her a year later and died on 30 April 1865. The burial ceremony was conducted by Rev Van Warmelo, who was still battling at that stage to cope with the death of his own wife three months before. Almost half a century after their deaths, on 9 September 1922, the remains of MacKidd and his wife were removed from the Goedgedacht farm and reburied at the Kranspoort mission station.

The angel of death not only knocked on the doors of the Dutch missionaries in the Soutpansberg. In 1869, two Swiss missionaries, Ernest Creux and Paul Berthoud, arrived in South Africa. The two started with their work in the then Basoetoeland and for the first three years worked under the auspices of the Paris Evangelical Missionary Society. In 1873, reverends Mabille and Berthoud took a journey to the north to see whether a missionary station could be opened. In the region known as the Spelonken they encountered the Shangaan people and realised that there was a need to work among this community.

On 9 July 1875, Creux and Berthoud, accompanied by their wives and children, arrived at what was later to become Valdezia. One of the first problems they had to overcome was the language barrier. At that stage, both missionaries could speak some Sotho, but they quickly realised that the local people spoke Chigwamba or Tsonga.

Despite all the difficulties, the Swiss men and women set about turning the somewhat inhospitable area into a mission station. A year later, when the first buildings were finished, more trouble arrived, but this time in the form of the Boer government. As previously mentioned, the ZAR did not take kindly to anyone wanting to teach the gospel to non-whites. Creux and Berthoud were arrested on 2 August 1876 and placed in protective custody. Their arrest caused quite a stir among the local white community and Rev Stephanus Hofmeyr was one of the people who petitioned the government to put an end to the “schandelijke daad” (scandalous deed).

Hofmeyr, at that stage the missionary at Kranspoort, often visited the Swiss missionary station and got along well with Creux and Berthoud. A group of 22 locals travelled to Marabastad, where the two were held, to demand their release. Fortunately, sanity prevailed and the government, under leadership of Pres T.F. Burgers, issued an instruction that the two clergymen be released and allowed to continue with their work.

In 1879 and 1880 a malaria epidemic struck, killing Mrs Berthoud and, one by one, all five her children. Rev Creux’s family was also not spared and three of his children died of diphtheria. Seeing that this article concerns Rev Van Warmelo, we should return to his role in the history of the Soutpansberg, and more specifically the eventual evacuation of the town Schoemansdal in July 1867.

The Schoemansdal people were quick to embrace the Dutch reverend and sympathised with his losses. In February 1866 Van Warmelo attended the church’s general assembly in Potchefstroom. When he returned the local congregation had put up a tombstone on his wife’s grave and planted a bed of roses around it.

Van Warmelo saw the need for proper tuition in the booming trade town and started classes for the children every weekday morning in the church hall. The inadequate facilities prompted him in April 1866 to write to the president of the ZAR, asking that a government school be established at Schoemansdal. He even identified an ideal candidate for the post as schoolmaster, namely Cornelis van Boeschoten, a young man who assisted him when teaching the children.

The construction of a school building remained a dream for Van Warmelo and it seems as this became a reality early in 1867, albeit with funds provided by the local church congregation. The reverend had to fulfil the role as building inspector, giving advice where necessary.

On 29 April 1867, Van Warmelo married Maria Maré, daughter of the then landdrost of the Soutpansberg, Dietlof Siegfried Maré. Van Warmelo was clearly a very popular and loved figure. In later years Senator G.G. Munnik, in his memoirs, writes very kindly about the man of the gospel:

“The Rev. Mr. Van Warmelo remained with his people in their wanderings, and became a veritable Moses to them. Everyone rushed to him with their joys, their griefs, and their sorrows.”

Life in Schoemansdal became increasingly more difficult with constant attacks by the Bavenda, under leadership of Makhado and his uncle, Khatelage or Katse-Katse. The fact that Makhado’s warriors were heavily armed with rifles previously used for hunting, did not help the town people.

The ZAR government was asked for urgent assistance and on 6 June 1868 commandant-general Paul Kruger arrived at Kranskop near the Nyl river with some 400 men. Kruger asked the president for a much larger force, but there seems to have been a general unwillingness among the burgers to report for duty. Many felt that the Schoemansdal people had caused their own problems by allowing rifles to end up in the hands of the Venda warriors. Many reasons were later put forward as to why Kruger’s efforts to save the town were unsuccessful. These include a serious lack of ammunition, dissention among troops and the fact that Katse-Katse’s fortress in the mountain was near impenetrable.

Kruger realised the imminent dangers and the proposal was made that the people be moved to a safer area. This proposal met with a lot of resistance and Rev Van Warmelo spearheaded a petition wherein some 60 residents vowed to fight to retain the town, but all was to be in vain.

On 12 July 1867 an order was issued that Schoemansdal must be evacuated. This created panic among residents and everyone tried to load as much of their belongings as they could onto wagons. Even Rev Van Warmelo only had time to remove the window frames and doors of the church. The lager moved out on 15 July and as the last wagons pulled away the Venda warriors started burning down the houses and knocking down the buildings.

The Schoemansdal people moved to Marabastad, some ten kilometres west of where Polokwane is situated at present. For the next year Van Warmelo stayed with part of his flock and a corrugated iron church was erected, but in the middle of 1868 he accepted a call to become minister of the congregation in Heidelberg. He stayed in Heidelberg for the remainder of his life.

In the latter part of his life Van Warmelo tried his best to unite the Nederduitsche Hervormde Kerk and the Nederduitsche Gereformeerde Kerk. Between the years 1882 and 1885 he was active in a number of commissions to try and unite the two biggest church bodies in the then ZAR. It was clearly a bridge too wide to cross and in 1891, after Pres Paul Kruger had arranged a meeting to try and settle the matter, it was clear that unity would not be achieved and the court was asked to adjudicate the further differences.

On 21 April 1892 Van Warmelo died at the fairly youthful age of 56. Doctors could not find a definite cause for his death, but ascribed it to the tension brought about by the ongoing feud within the church bodies.

Of the once bustling town of Schoemansdal, very little is left. In the little graveyard the remains of 122 people who died during the period, mostly after contracting malaria, rest peacefully. In 1917, fifty years after the evacuation, a brick wall was built around the graves. Mrs Van Warmelo’s grave was one of the many that was vandalised and destroyed by floods and elements of nature. The Louis Trichardt congregation of the Hervormde Kerk replaced the headstone some years later.

Sources:

* Maree, W.L. Lig in Soutpansberg. Voortrekkerpers Bpk, 1962.

* De V. Pienaar and associates. Neem uit die Verlede. Nasionale Parkeraad, 1990.

* De Waal, J.J. Schoemansdal: ‘n Voortrekkerdorp 1848-1868. Thesis for doctor’s degree Unisa, Feb 2000.

-

14. The meeting place of opposing ideologies

22 December 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

13. JC Krogh – The maker of peace?

28 October 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

12. Tracing the origins of the first Indian traders in the Soutpansberg

30 September 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

11. The (secret) story that started with Piet Retief

01 August 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

10. The times were a’changin for a controversial president

20 June 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

-

8. The casualties of war for the souls of the Soutpansberg

18 April 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

7. Bvekenya Barnard - the most famous of Crook’s Corner’s elephant hunters

21 March 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

6. The Englishman who helped shape the course of the country’s laws

29 February 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

5. Piet de Vaal, the stately “baobab” of the Soutpansberg

15 February 2016 By Anton van Zyl

ADVERTISEMENT