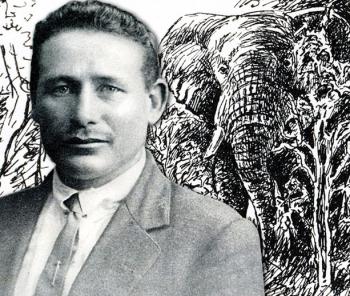

7. Bvekenya Barnard - the most famous of Crook’s Corner’s elephant hunters

Date: 21 March 2016 Viewed: 24188

Part of Bulpin’s story plays out in the northern-most corner of the country, more precisely at the spot where South Africa, Mozambique and Zimbabwe meet. “Crooks Corner is the name man gave long ago to this secluded and sinister wedge of land. It was a last home for many a curious and lawless character: a sanctuary from civilisation, whose solitary state was paradise to all those whose deeds or inclinations made imperative a retreat to some last stronghold of the lawless,” writes Bulpin.

Unlike a Hollywood film script, Bulpin’s depiction of this rugged and eccentric hunter is very authentic. The legendary Bvekenya was real and left an indelible mark on the region. It is said that even today the Shangaan people on the Mozambican side of the Save River still wait for Barnard and that the land will not be made available for hunting to anyone else, as it is “Bvekenya’s land.”

A couple of unfortunate events occurred in the years that followed. The area was hit by an outbreak of rinderpest and old man Barnard had to work away from home in trying to provide for the family. This was followed by the Anglo Boer War and, as a resident of the Boer Republic, Barnard Snr had to join the fight. This, of course, left Mrs Barnard and the children to fend for themselves under extremely difficult circumstances. When his mother was moved to a British concentration camp, Bvekenya had to look after his siblings. She died of sickness in the camp before her husband could return from the war.

In 1910, the same year that South Africa became a Union, Bvekenya set out with a wagon and donkeys along the Great North Road. At Soekmekaar (nowadays Morebeng), he turned north-east to Klein Letaba and from there the trail went to Punda Maria. Further north he crossed the Luvhuvhu River and arrived at the infamous Crook’s Corner.

Crook’s Corner had a number of rather interesting characters. Among the few friends that Bvekenya made were the owner of the Makhuleke Store, Alec Thompson, as well as a “blackbirder”, William Pye. Blackbirders made their money out of recruiting local tribesmen to work on the South African mines. Bvekenya himself later added to his income by working as a blackbirder.

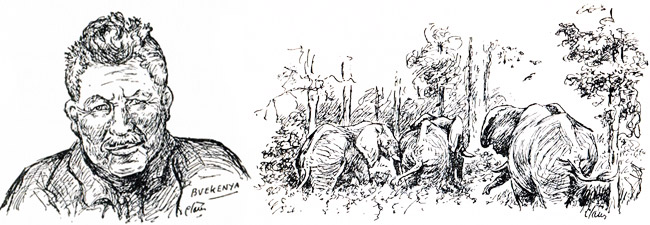

(Illustrations by C.T. Astley Maberly from The Ivory Trail, 1954)

The story goes that Bvekenya initially tried to hunt in a legal way and travelled to Massangena in what we now know as Mozambique, to obtain a permit. He was not successful and only obtained permission to hunt small game. One of the policemen stationed at Massangena, however, collected a gang of renegades and tried to rob and kill Bvekenya while he was camping near the Save River. Bvekenya managed to escape with only his cotton underpants on and had to walk back to Makhuleke, almost 240 kilometres away.

It was a long and dangerous journey and Bvekenya nearly succumbed on the way back. He was rescued by a group of Shangaan workers returning from the South African mines. They gave him a spear, some clothing and helped him to recover. They also gave him his name, which means “the man who swaggers when he walks”. This was probably because of the way he walked barefoot on the warm sand.

Bvekenya finally made it back to Crook’s Corner, where he used his wagon as collateral to borrow money to return to Johannesburg. He then kitted himself out in a more proper way and bought a 9.5 Mannlicher-Schoenauer, a weapon much more suited for shooting elephants.

Much of Bulpin’s story concerns Bvekenya’s quest for revenge and also to repay those who had been kind to him. Whenever he shot an elephant, the tusks were cut out and the rest of the meat went to the local villagers. In several instances his hunting skills and generosity saved them from starvation, especially during the early 1910s when the eastern region suffered from a terrible drought. The story also focuses on his obsession to shoot an exceptionally big elephant bull, called Dhlulamithi (taller than the trees).

Even though Bvekenya was an infamous poacher and fugitive from the law, he was also a conservationist. He did not believe in killing game for fun and always ensured that nothing that he had shot went to waste. His trackers had to ascertain the age of the elephant, often by studying the dung, to make sure it was past its prime.

During a trip to the then Rhodesia via the Lundi River, he witnessed the abundance of game congregating in the area, following the good rains. This made such an impression on him that he wrote to the Native Commissioner of Chibi in the Fort Victoria district, proposing that they establish a transfrontier park. Much to his surprise the Native Commissioner, a Mr P Forrestal, wrote back, thanking him for the letter and information, but he reckoned the authorities would not agree to such a proposal. It would take almost another 100 years before this idea became a reality.

Bvekenya gradually took revenge on his attackers and, in doing so, also collected warrants for his arrest in three countries. To the local inhabitants, however, he became a hero and a mystical legend. His ability to live off harsh, drought-stricken land, was unparalleled. Bulpin describes it as follows:

“The wilderness in which Bvekenya hunted, between the Great Sabi and the Limpopo, from the Rhodesian border down to within fifty miles of the sea, was known to the Shanganes as the Hlengwe (The Place Where You Need Help). It was a place where terror dwelt: a haunt of the wild animals, of sudden death, of an ancient savagery, and the nameless ghosts of strange gods whose lore and rites were half-forgotten.”

During his almost 20-year stay in the area, Bvekenya studied not only the animals in the area, but also the plants and trees. He experimented with taming the eland and even sent some as gifts to the national zoo.

As “blackbirder” Bvekenya’s name was known far and wide. This was a very controversial “occupation” and often accompanied by tales of abuse and deceit. Tribesmen were lured from various villages to work in the mines in places such as Johannesburg and Kimberley, often under atrocious circumstances. The blackbirders received up to £7 for every recruit, which made it a very profitable business.

Bvekenya had a very organised and almost sophisticated system in place to guide the recruits to the mines. These included several hidden bush camps en route, where the men could rest and eat and could also acclimatize as they travelled southwards. One of the biggest dangers for mine workers coming from northern countries was pneumonia. They were simply not ready to face the damp, cold conditions in the Highveld mines.

During his years in the Soutpansberg, Bvekenya made several good friends. When Thompson departed, the Makuleke store at Crook’s Corner was managed by a Canadian, Buck Buchanan. Buchanan later moved to a farm close to the Soutpansberg. Another friend of Bvekenya’s was Hendrik Hartman and the two of them agreed to farm with sheep at the back of the Soutpansberg. In 1918, Hartman was in Crook’s Corner, busy building a kraal for the sheep, when he climbed up a large thorn three to cut down branches. As he worked his way up the tree, the branches formed a pile below him. When he at last realised that he had left no escape route, it was too late and he could not get down. He shouted for help, but had to spend the day up there before help arrived. He died of sunstroke a few days later and was buried at Crook’s Corner.

Bvekenya often visited Louis Trichardt, where another hunter friend of his, Hans Klopper,lived. Klopper farmed at Doornspruit near the town, but his favourite hunting ground was in the northern parts of the Kruger National Park. An area with a fountain just north of the Shantangalani hills, Klopperfontein, is named after him.

Towards the end of his “career” as blackbirder, Bvekenya became a more law-abiding citizen and worked for a mining company, officially recruiting workers. This only lasted until 1923 when the call of the bush became too much for him to tolerate. For the next few years he was back hunting elephants, but the circumstances had changed. He was appalled by the manner in which Africa’s resources were being destroyed, especially by those with no knowledge of the bush. At the same time, several national parks were declared and policing of these areas intensified.

In 1929, at the age of 43, Bvekenya left the area where he had had so many adventures and close encounters with death. He bought a farm in the western Transvaal at Geysdorp. He married Marie Badenhorst and they had four sons and a daughter.

Bvekenya only returned to the Soutpansberg twice in his later years. During the first visit, in 1952, he took his son, Isak, to show him the old places. On the second occasion he took the author, T.V. Bulpin, to Crook’s Corner. Bulpin’s book, The Ivory Trail, first appeared in 1954.

Fun Trivia: Does he look familiar? He may remind you a little of Martin Henderson, an actor born in New Zealand. Do you agree?

-

14. The meeting place of opposing ideologies

22 December 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

13. JC Krogh – The maker of peace?

28 October 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

12. Tracing the origins of the first Indian traders in the Soutpansberg

30 September 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

11. The (secret) story that started with Piet Retief

01 August 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

10. The times were a’changin for a controversial president

20 June 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

-

8. The casualties of war for the souls of the Soutpansberg

18 April 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

7. Bvekenya Barnard - the most famous of Crook’s Corner’s elephant hunters

21 March 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

6. The Englishman who helped shape the course of the country’s laws

29 February 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

5. Piet de Vaal, the stately “baobab” of the Soutpansberg

15 February 2016 By Anton van Zyl

ADVERTISEMENT