3. Songozwi - once the den of the Lion of the North

Date: 08 January 2016 Viewed: 24816

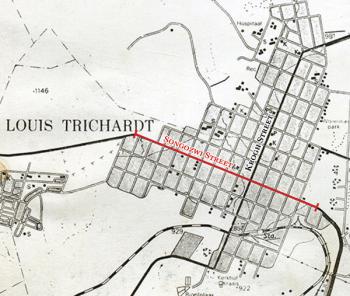

In this week’s column we look at one of the “new” street names, albeit one of the oldest streets in town. Songozwi Street used to be called Trichardt Street and it was one of the first streets to be renamed following the 1994 elections.

Songozwi can refer both to the mountain (towards Hanglip as it is nowadays called) or the adjacent Songozwi village (Luatame) on top of the mountain. From a historical point of view it is a very interesting place with quite a colourful history. Up to the end of the 19th century this used to be the area where the Royal House of the Vhavenda had been situated, an almost impenetrable fortress surrounded by a lush indigenous forest.

The beauty of the area was quite aptly described in a report filed in 1883 by the Swiss missionary, Ernest Creux. He was asked by the Boer forces commander, Christiaan Joubert, to speak to King Makhado and re-establish peace. A somewhat unwilling Creux embarked on the 18 kilometre route from Elim, crossing the “no-go” area and made his way up the mountain. His path took him through “the sacred forest of the ancestral spirit gods of the Ramapulana.” In a rather humorous remark he states “I do not think I could have stood the heat without my umbrella”.

Creux’s description of Songozwi is very picturesque:

“Flowers of all sorts send their perfume over the hills; mint, blue and white violets, gigantic yellow and white flowers, and tree ferns grow in the clearings and the forest … The path now follows the slope, crosses singing brooks, which lower down either turn into waterfalls, or run in the thick forest. Oh what a beautiful country!”

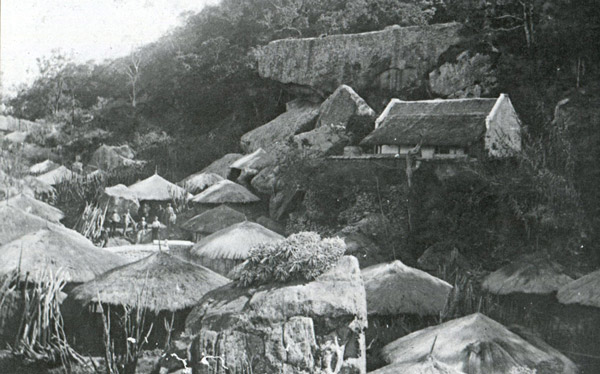

Luatame was an organized capital, benefitting from the presence of the sheer rise of the mountain behind it and its limited accessibility. The mountain had numerous streams, fed by condensation from the cliffs, and this insulated the kingdom against drought and kept the soil rich and productive. A series of walled passages and village areas helped to maintain the hierarchical order.

Songozwi, however, was not the original “head-quarters” of the Vhavenda. Most historians agree that the first real king of the Vhavenda was Dimbanyika, leader of the Vhasenzi who arrived in the area in the early 1700s. The Vhasenzi subjugated the different clans such as the Vhangona who resided in the area. King Dimbanyika’s royal palace was first established at Dzata I, on Mount Lwandali in Nzhelele.

The idyllic spot where the Kings Ramabulana, Makhado, and Mphephu reigned.

Dimbanyika died in 1722 and was succeeded by Vele-la- Mbeu. Mbeu was succeeded by probably one of the greatest of the Vhavenda kings, Thohoyandou. Thohoyandou deployed his son, Munzhedzi Mpofu, to the area called Luatame on Mount Songozwi.

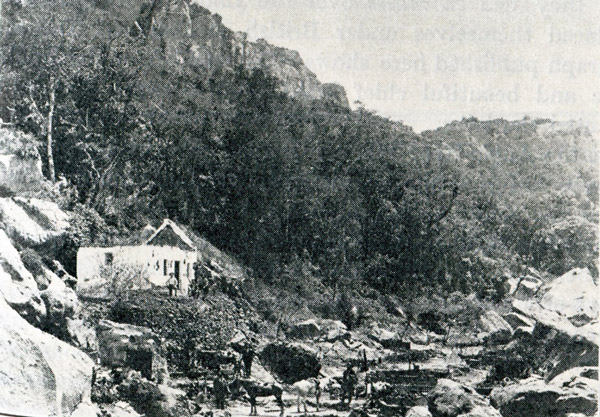

When King Thohoyandou disappeared without a trace in 1770 it caused a battle for succession (as has become customary). The eventual winner (after some bloody battles), was Mpofu and he relocated the royal kraal from Dzata to Songozwi. Songozwi was strategically very well situated, as one could see the whole kingdom from the summit and it offered ideal protection against advancing armies. Below the mountain was Tshirululuni, the grazing fields for the cattle where the town Louis Trichardt was later laid out.

The kings that followed after Mpofu continued to use Songozwi as a stronghold, to good effect. King Makhado, often referred to as the Lion of the North, used Songozwi as a base to organise his attacks on the expanding Boer settlement at Schoemansdal. This was so effective that Schoemansdal had to be evacuated in 1867.

In spite of various attempts to drive him out of his stronghold at Luatame on Mount Songozwi, Makhado remained relatively unscathed. He was, however, someone who kept communication channels open with his enemies and earned the respect of Boer leaders such as Cmdt Piet Joubert and the then landdrost of the district, GC Munnik.

When Makhado died on 3 September 1895, possibly after being poisoned by some family members, another succession battle followed. Before his death he indicated that his youngest son, Maemu, should be the next king, but this did not happen. Following some serious skirmishes, Alilali Tshilamulela was installed as king and given the title of Mphephu.

Whereas Makhado was a very effective diplomat who managed to avoid direct conflict while at the same time stand firm on what he believed in, Mphephu was perceived to be arrogant and not the legitimate ruler. His regular contact with the British forces also did not help foster good relationships with the government of the day, the ZAR. The interference of the British, even during the reign of Makhado, was viewed with suspicion by the Boer forces.

Matters gradually got worse and worse and several of Mphephu’s family members openly turned against him. His refusal to allow land surveyors in the area also did not go down well with the ZAR. In October 1898 the ZAR tasked Commandant General Piet Joubert to put an end to the conflict and on 17 October he gathered with some 1 000 burgers at the foot of the mountain. Joubert sent letters to other mahosi asking for their support and ordered more burgers to join the battle.

On 16 November 1898, in a carefully executed operation, Joubert’s forces along with Swati and Shangaan regiments, stormed the capital. It is very likely that Mphephu had prior knowledge of the attack and was aware of the capabilities of the attacking force. He fled, along with most of his supporters to the north. Three days later the Boer forces dynamited the capital as well as the surrounding settlements.

The scene at Songozwi village after the war against Mphephu in 1898.

The story of Songozwi village, however, did not end here. Mphephu and his followers sought refuge in Southern Rhodesia, where they were protected by the British South African Constabulary (BSAC). After the Anglo Boer War Mphephu returned, but not much came of the promises of the return of his land. His relationship with the notorious Captain Alfred “Bulala” Taylor may also have been a strategic mistake, as the British official had turned against him.

It seemed inevitable that the British government, as was the case previously with the ZAR, was set on the colonization of “Magatoland”. Reserves for the “Ramabulanas” were mapped out towards the western side of the mountain, while at the same time Boer farmers were taking up vacant land in and around the mountain.

Mphephu started petitioning the British government, requesting permission to return to his land. This caused a mixture of opinions, and political confusion. As Lyndsay Braun writes: “… Mphephu’s ongoing exile offered a powerful symbol of British hypocrisy and injustice, given that they permitted his other enemies and even their own Boer foes to live freely in the Colony.”*

Mphephu eventually agreed to be re-established in an area in Nzhelele, and many mahosi and their immediate communities moved there. His brothers, Sinthumule, Maemu and Kutama settled in the flat sections south of the mountain.

There was still a reluctance from Mphephu to vacate Songozwi and during 1905 he resided in a house at Luatame. The house was pulled down by the SA Constabulary in September of that year and Mphephu was instructed to vacate the capital in its entirety.

A legal battle followed and Mphephu, represented by an attorney from Pretoria, CP Bawden, tried to persuade the British Government to allow them to stay ay Luatame. This also had limited success, but at least secured Mphephu the right to retain the royal burial ground on Songozwi where, among others, Makhado had been buried. This was, interestingly enough, only allowed in March 1907 by the first Prime Minister of the Transvaal Colony, former Boer general Louis Botha. The government set aside about 160 acres for five families of Mphephu’s choosing to stay in the area near the ancestral graves.

Today Songozwi is still a stunningly beautiful site and it has retained its ancestral identity. The atmosphere was somewhat marred when the government allowed RDP houses to be built adjacent to the burial grounds in 2009. The houses next to the burial sites, however, are still thatched roof huts.

Sources:

* Braun, L.F. “Colonial Survey and Native Landscapes in Rural South Africa, 1850-1913” Brill 2015

* Nemudzivhadi, M.H. “The Attempts by Makhado to Revive the Venda Kingdom 1864-1895”, Potchefstroom University for CHO 1998.

* http://www.luonde.co.za/songozwi.html

-

14. The meeting place of opposing ideologies

22 December 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

13. JC Krogh – The maker of peace?

28 October 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

12. Tracing the origins of the first Indian traders in the Soutpansberg

30 September 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

11. The (secret) story that started with Piet Retief

01 August 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

10. The times were a’changin for a controversial president

20 June 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

-

8. The casualties of war for the souls of the Soutpansberg

18 April 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

7. Bvekenya Barnard - the most famous of Crook’s Corner’s elephant hunters

21 March 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

6. The Englishman who helped shape the course of the country’s laws

29 February 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

5. Piet de Vaal, the stately “baobab” of the Soutpansberg

15 February 2016 By Anton van Zyl

ADVERTISEMENT